Immigration

Immigration in the United States

Immigration has been a foundational and transformative force in shaping the demographic composition, political discourse, and cultural identity of the United States. From its earliest colonial days, the U.S. attracted primarily European settlers, mainly from England, Ireland, Germany, and other Western and Northern European countries. These initial populations established the social, political, and economic frameworks of the young nation. Over the centuries, waves of immigration continued, each influenced by the prevailing economic conditions, political upheavals abroad, and evolving American policies. While early immigration was predominantly European, subsequent waves brought increasing numbers of individuals from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as Asia and Latin America. For most of American history however, immigration was heavily limited to only Whites. Any framing of the narrative that claims we are a nation of immigrants without addressing this fact is highly disingenuous.

America was always intended to be a melting pot of European ethnicities, IT WAS NEVER INTENDED TO BE A RACIAL MELTING POT.

Early Immigration Policy and Restrictions

The history of U.S. immigration law reveals a pattern of racial and ethnic exclusion intended to shape the nation's demographic makeup in accordance with dominant social hierarchies of the time. Early federal policies codified these biases, often explicitly prioritizing White European populations and restricting non-White immigration.

1790 Naturalization Act

The Naturalization Act of 1790 was the first federal statute governing the process by which immigrants could become American citizens. Crucially, it limited citizenship to "free White persons of good character," effectively codifying a racial prerequisite for naturalization and excluding Native Americans, African Americans, Asians, and other non-White groups. Additionally, the law restricted naturalization rights to men, explicitly excluding women from the process regardless of race. This racialized citizenship framework established by the 1790 Act set a precedent that influenced subsequent immigration and naturalization policies, reinforcing a conception of American identity grounded in White European ancestry. Access to citizenship would become more expansive over time; although, the racial restriction was not eliminated entirely until 1952. 1

1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first significant federal legislation to impose immigration restrictions based explicitly on ethnicity and nationality. It prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers for a ten-year period. For the first time, federal law proscribed entry of an ethnic working group on the premise that it endangered the good order of certain localities.2 This law not only suspended new Chinese immigration but also placed severe restrictions on the rights of Chinese immigrants already residing in the U.S., barring them from citizenship and limiting their legal protections. The Act was extended multiple times and remained in effect until its repeal in 1943, laying the groundwork for further exclusionary policies against other non-European groups.

1924 Johnson-Reed Act

Also known as the Immigration Act of 1924, the Johnson-Reed Act established a national origins quota system designed to preserve the existing ethnic composition of the United States, which was predominantly Northern and Western European at the time. The law severely restricted immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe and barred immigration from Asia entirely.3 The quota system assigned visas based on the proportion of each nationality present in the U.S. according to the 1890 census, deliberately favoring groups deemed more "desirable" by the racial and ethnic standards of the era. This legislation institutionalized racial and ethnic hierarchies in immigration policy and had lasting effects on the demographics of the American population, virtually halting immigration from Asia and significantly reducing numbers from Southern and Eastern Europe.

1965 Hart-Celler Act

The Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1965, commonly known as the Hart-Celler Act, represented a dramatic shift in U.S. immigration policy. The Act abolished the national origins quota system established in 1924, replacing it with a preference system based on family reunification and skilled labor qualifications. Although framed as a more equitable and moderate reform, the Hart-Celler Act unintentionally precipitated profound demographic changes by opening immigration channels to countries in Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Caribbean. This resulted in increased immigration from these regions, diversifying the U.S. population ethnically and culturally. The legislation reflected Cold War-era geopolitical considerations and a growing recognition of civil rights but also introduced new challenges in assimilation and social cohesion debates. The Hart-Celler Act remains the foundation of contemporary U.S. immigration law and continues to shape patterns of migration and national discourse about identity and belonging.

Origins of the Statue of Liberty's "Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor" Engraving

The famous engraving on the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal, featuring the lines "Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free," originates from a poem titled *"The New Colossus"* written by American poet Emma Lazarus in 1883. Emma Lazarus was a Jewish-American poet and essayist known for her advocacy of Jewish refugees and immigrants. At a time when the United States was experiencing growing waves of immigration, particularly from Eastern and Southern Europe, Lazarus’s work reflected empathy toward those seeking refuge and opportunity in America. In 1883, the New York-based organization “The Bartholdi Pedestal Fund” commissioned Lazarus to write a poem to help raise funds for the construction of the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal. The statue itself, a gift from France symbolizing freedom and democracy, was nearing completion, but financial resources for its base were insufficient. Lazarus wrote *"The New Colossus"* as a sonnet contrasting the Statue of Liberty with the ancient Colossus of Rhodes. Unlike the latter, a symbol of conquest and power, Lazarus’s statue was cast as a welcoming "Mother of Exiles," offering refuge to the oppressed.

The specific lines engraved on the pedestal are from the final stanza of the poem:

"Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

These words encapsulate an idealized vision of America as a sanctuary for immigrants and refugees, emphasizing compassion and opportunity. Although *"The New Colossus"* was not initially widely associated with the Statue of Liberty, the poem gained prominence in the early 20th century as immigration surged through Ellis Island, located nearby in New York Harbor. In 1903, a bronze plaque inscribed with Lazarus’s poem was installed inside the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal, cementing the connection between the statue and the message of welcome and refuge. Since then, the poem’s lines have become emblematic of America’s self-image as a nation of immigrants, frequently cited in political and cultural discourse concerning immigration policy and national identity.

However, it is important to note that the poem's welcoming message contrasts with many restrictive immigration laws historically enacted by the United States, reflecting ongoing tensions between ideals and policy realities.

Projected Demographic Impact

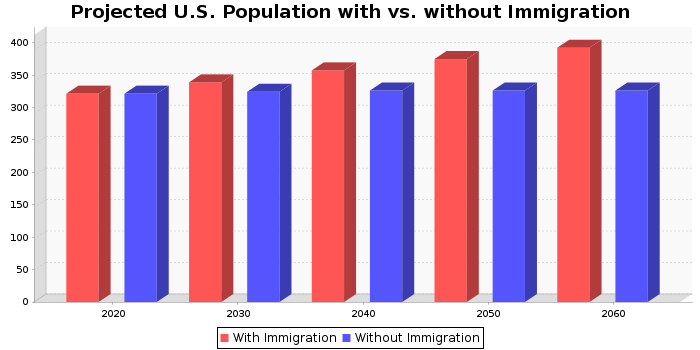

Recent projections by Camarota & Zeigler (2022) reveal that immigration is responsible for nearly 90% of future U.S. population growth, with long-term consequences for infrastructure, schools, and entitlement programs.

| Year | With Immigration | Without Immigration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 331 | 331 | |

| 2030 | 349 | 334 | |

| 2040 | 368 | 336 | |

| 2050 | 386 | 336 | |

| 2060 | 404 | 336 |

Fiscal, Political, and Social Consequences

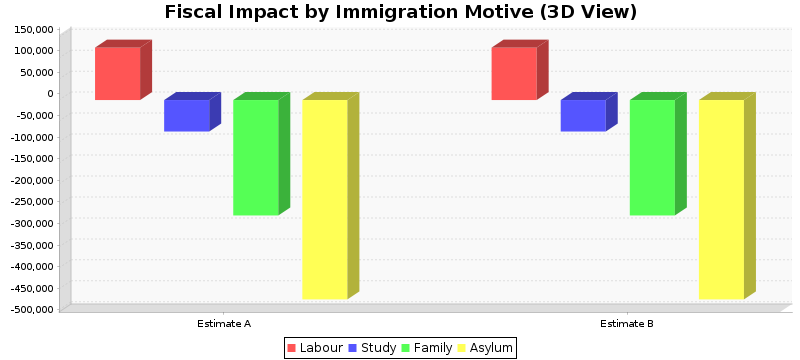

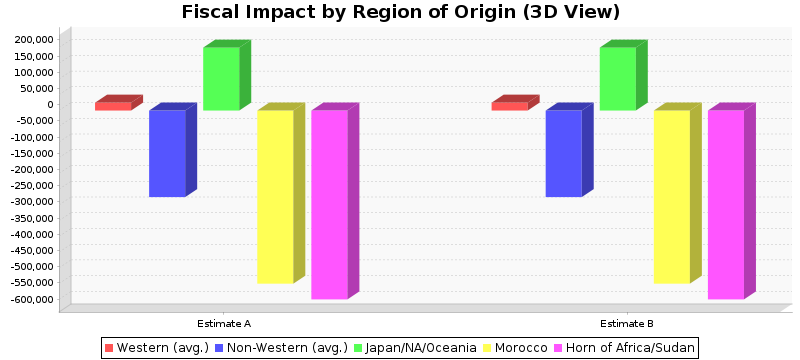

Immigration is no longer just a cultural phenomenon. As shown by multiple empirical studies, it carries measurable fiscal burdens, reshapes voting patterns, and introduces new demands on state institutions.

Immigration and the Fiscal Burden on the Dutch Welfare State

The 2023 report Borderless Welfare State presents a comprehensive analysis of immigration's impact on Dutch public finances. Between 1995 and 2019, immigration—including the second generation—incurred a net fiscal cost of approximately €400 billion. Projections indicate that, if current patterns continue, this figure could exceed €1 trillion by 2040.

This cost arises from increased per capita spending on education, healthcare, social security, and justice services for immigrants, combined with lower average tax contributions. In 2016 alone, the net fiscal cost of immigration peaked at €32 billion.