Do Blacks use drugs at the same rate as Whites?

Blacks and whites do not use drugs at similar rates, blacks just lie about not using drugs at high rates.

When discussing the issue of Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

, one argument that comes to its support of its existence is how there is a racial bias in drug arrests. This argument argues that multiple studies have found that blacks and whites tend to use drugs at similar rates, but whites are less likely to be arrested for drug offenses than blacks. This disparity between drug use and arrests by race has been argued to be due to systemic racism in the criminal justice system. In this post, I’ll argue that this disparity has nothing to do with racism, and that instead racial differences in drug use and purchasing is responsible for the racial disparity.

These studies get a large sample, and then ask the respondent if they have ever used drugs recently. From there, they usually compare drug use by race to arrest rates for drug offenses by race. So the first part (asking about drug use) is based on Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

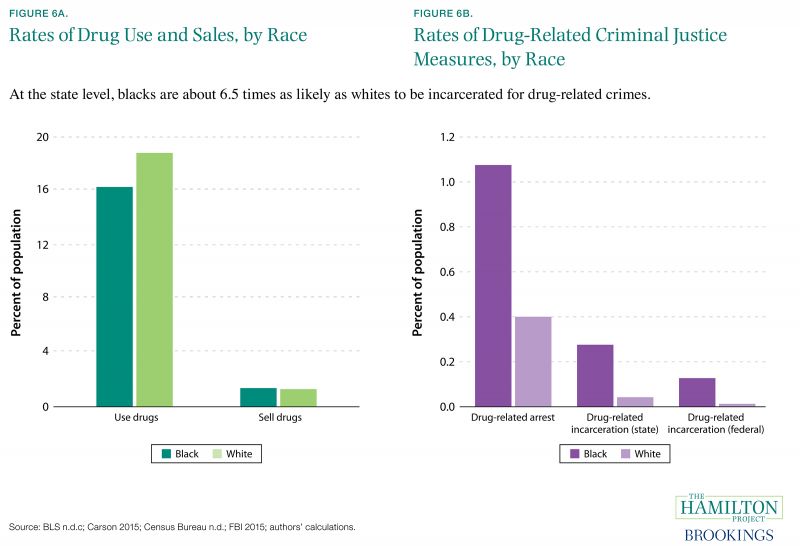

First and foremost, it is true that studies have found that blacks and whites use drugs at similar rates, or that blacks have higher or slightly lower drug use than whites, but blacks are arrested more often for drug offenses. For example, Johnston et al. (2002) 1 looked 43,700 students and gave them a questionnaire that asks about their drug use. According to Johnston et al., “Use also tends to be much higher among White students than among African American or Hispanic students” (p. 6). Schanzenbach et al. (2016) 2 reported that whites have a higher rate of drug use, as can be seen in the chart below, but black are arrested at higher rates.

Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

Using data from Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

, the Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

reported that blacks report slightly higher cannabis use in the past month and past year, but whites report higher lifetime usage (50.7% for whites compared to 42.4% for blacks). Even though whites seem to use cannabis at higher rates overall, blacks are still arrested at higher rates for drug use (Edwards et al. 2020). 3 Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

Human Rights Watch (2009) 4 remarked that blacks are more likely to be arrested for drug offenses, but this can not be pinned onto higher drug use among blacks since blacks and whites use drugs at similar rates (Gorvin 2008) 5 Edwards et al. (2003) 6 found similar results as the above 2020 revised report, and they offer a chart which seems be used quite often when discussing this issue:

Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

Utilizing a Probability-based sampleUnknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

of 4,580 college students who completed an online questionnaire, McCabe et al. (2007) 7 found that Hispanic and white students reported higher drug use in college and before entering college when compared to blacks and Asians. The evidence seems quite clear, and to some only a fool would deny this as many analysis have found blacks to be more likely to be arrested for drug use even though nationwide data shows similar rates of drug use (see Owusu-Bempah and Luscombe 2020 8; Hughes 2020 9; SPLC 2018 10; see the report by the Justice Policy Institute 11, too). Many commentators, like the Youtube political commentator Vaush 12 and the political pundit Van Jones (in Emery 2016 13), have echoed these findings as proof of systemic racism in the criminal justice system.

Despite the overwhelming evidence showing this to be the case, these disparities are not a result of systemic racism. The null hypothesisUnknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

should not be that racism is to blame for these racial disparities, but rather it should be racial differences in how different racial groups use drugs and how often they do it. In reality, there is no reason to assume that the above findings are accurate for two strong reasons: \[1] blacks are more likely to lie on self-report surveys, especially those that deal with crimes, and blacks are more likely to lie about their drug use when compared to whites, thus artificially decreasing their actual drug use rates; \[2] racial differences in drug consumption can explain why blacks are more likely to be arrested for drug offenses, even if drug use by race is similar or lower for blacks.

Dealing with the first line of counter-evidence, criminologists have found that blacks are more likely to underreport their actual crime rates when asked. According to Cernkovich, Giordano, and Rudolph (2000: 143) 14, there is “evidence that black males’ self-reports of delinquency are less valid than the reports of other groups: Black males underreport involvement at every level of delinquency, especially at the high end of the continuum.” Hindelang, Hirschi, and Weis (1981) 15 report that self-reports are less valid for groups like blacks, with similar findings being remarked by Huizinga and Elliott (1986) 16. Due to this, there is no reason to assume that blacks are being honest about their drug use. Although this is for crime in general, the same is true for drug use specifically. Page et al. (2009) 17 did a Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

tests and asked the people in their study if they have used drugs recently.

Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

After running a linear model, it was found that non-whites were more likely to say they have not used drugs recently when they in fact did. Falck et al. (1992) 18 looked at 95 drug users and had them do a urine test after asking them if they had used drugs recently. In Table 3 they found that blacks were more likely to falsify their self-reports on opiate and cocaine use, as seen in the table below.

Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

Feucht, Stephens, and Walker (1994) 19 looked at 88 juvenile arrestees and had them do a hair test and urine analysis. In their urine analysis, blacks were more likely to lie about not using cocaine when they in fact did, as argued by Feucht and his colleagues when they said that “However, the higher rate of urinalysis cocaine-positive results for black arrestees suggests that the higher hair assay levels may actually indicate greater use of cocaine among the black arrestees in the sample.” Looking at marijuana, Fedrich and Johnson (2005) 20 found a lower Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

rate within blacks, with the same being true for cocaine use. Other studies have also found that blacks and non-whites are more likely to report lower drug use, even though testing them shows that they’re lying (see Miyong, Hill, and Martha 2003 21; Ledgerwood et al. 2008 22; Fendrich and Xu 1994 23).

Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

Moving onto point two, this can also explain the disparity in drug arrests either in conjunction with point #1 or as a stand alone point. Let’s say that the self-reported data is accurate, and that whites and blacks do use drugs at similar rates or even slightly higher-but not enough to explain the disparity-rates. Blacks being more likely to be arrested for drugs can be explained by racial differences in drug consumption and how they go about purchasing drugs. Ramchand, Pacula, and Iguchi (2006) 24 noted that “African Americans are nearly twice as likely to buy outdoors (0.31 versus 0.14), three times more likely to buy from a stranger (0.30 versus 0.09), and significantly more likely to buy away from their homes (0.61 versus 0.48).” This shows that blacks are more reckless when buying drugs since it seems they’re more likely to buy it from someone they don’t know and use it outdoors where they can be caught, especially since these Unknown macro: tooltip. Click on this message for details.

have higher crime rates where there is more police presence and blacks use drugs in areas with higher crime rates (Lagan 1995) 25. Race differences in consumption and purchasement can explain the disparity, but the racism hypothesis relies on self-reported data which seems to be inaccurate.

In conclusion, racism can not explain why blacks are more likely to be arrested for drug offenses. As has been noted above, these studies rely on self-reported data in which blacks are more likely to lie on than whites. The fact that drug testing shows opposite results from what places like the ACLU argue should cast strong doubt on the racism hypothesis. Racial differences in drug use and consumption also show that race differences in these areas can explain why blacks are more likely to go to jail for drug offenses than whites, even if drug use by race was similar or slightly higher for blacks. Purveyors of the racism hypothesis have yet to dispute these findings, instead relying on flawed methods of proving racism for racial differences in drug arrests.

Sources

Much of the original content sourced from: https://raceandconflicts.home.blog/

- ^ https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/137799

- ^ https://www.brookings.edu/articles/twelve-facts-about-incarceration-and-prisoner-reentry/

- ^ https://www.aclu.org/publications/tale-two-countries-racially-targeted-arrests-era-marijuana-reform

- ^ https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/03/02/decades-disparity/drug-arrests-and-race-united-states

- ^ https://www.hrw.org/report/2008/05/05/targeting-blacks/drug-law-enforcement-and-race-united-states

- ^ https://www.aclu.org/files/assets/1114413-mj-report-rfs-rel1.pdf

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2377408/

- ^ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33011019/

- ^ https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/Albany-police-s-marijuana-enforcement-continues-15438317.php

- ^ https://www.splcenter.org/20181018/alabamas-war-marijuana#fiscal-cost

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20200710144922/http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/vortex.pdf

- ^ https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ido70LgXsEhxcnyXE7RVS0wYJZc6aeVTpujCUPQgTrE/mobilebasic

- ^ https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2016/jul/13/van-jones/van-jones-claim-drug-use-imprisonment-rates-blacks/

- ^ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0022427800037002001

- ^ https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=79068

- ^ https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01064258

- ^ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/10826087709027235

- ^ https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/aids/21/

- ^ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/002204269402400106

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3455900/pdf/11524_2006_Article_433.pdf

- ^ http://www.readabstracts.com/Sociology-and-social-work/Validity-of-self-report-of-illicit-drug-use-in-young-hypertensive-urban-African-American-males.html#b

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2495080/

- ^ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7960302/

- ^ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16600529/

- ^ http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rdusda.pdf